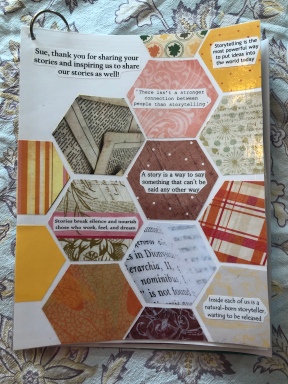

Look at this beautiful book of stories. This was gifted to me by folks who work at a disability agency. They were a recent client of mine.

I was on an eight-month contract to do an assessment of the level of the family engagement at the organization. I had conversations with families, staff and partners about ideas to better support young families as they navigated the minefield of systems when their child is first diagnosed with a disability or delay.

This is all fancy-sounding talk for I went for coffee with lots of people and listened carefully to what they had to say. Everybody spoke in stories. Then I compiled their ideas and put them in a report along with recommendations for positive change. I was merely a vessel for their stories.

When I started in the family centred care field a dozen years ago in a children’s hospital, I only thought of stories in terms of the family and youth stories. I learned that professionals have a need to tell their stories too. For stories are what make us all human. In fact, stories are how we communicate about ourselves. We don’t refer to ourselves in terms of data or numbers. We use words (or photographs or visual art or dance or music or film…) to share pieces of ourselves with others.

I finally figured out that staff engagement and family engagement need to happen at the same time. You cannot have one without the other. That means that staff must have a safe place to tell their stories too. If they don’t, they sometimes hang onto their own stories in unhealthy ways and this can interfere with demonstrating empathy and providing compassionate care or service. Telling your story can set you free.

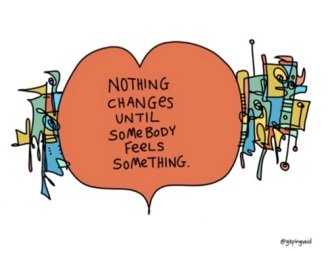

In health care, sharing stories happens in what is called reflective practice. In my layperson terms, reflective practice is sharing a story about something that happened, figuring out what you learned from it and making a plan to do things different next time. Sadly, reflective practice is rarely a priority in overly busy and frantic workplaces. Being still and simply listening to each other is becoming a lost art. Let’s start a movement to bring it back.

Reflective practice can be adapted to any kind of work environment. Facilitating reflective practice sessions with those in caring professions is one of my favourite things to do.

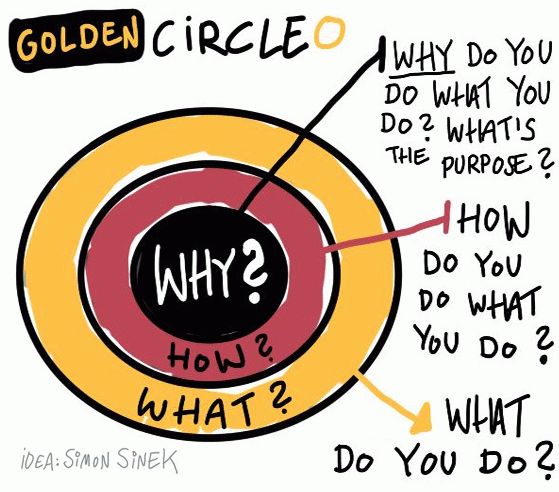

I start easy with icebreakers, asking round table questions like: what’s the story behind your name? Once trust is established within a group, we work up to sharing stories about the stories behind why they chose their profession. These types of stories really get to the heart of why people do what they do. Colleagues find out full ‘origin’ stories that go beyond where their workmates went to university. Pieces of hearts are slowly shared.

This can lead into facilitated conversations about what are their challenges working with patients or clients or families. I don’t offer solutions. I listen carefully and sometimes reframe questions. Sometimes I’ll tell a bit of my own story as a mom of a disabled child or as a cancer patient to provide a different perspective. Often someone else in the group has a good idea to share with their colleagues. Many times people know the answer to their challenges in their own hearts. Sometimes people just need a bit of space to unlock it.

There are many other formal ways to nurture storytelling and reflective practice. Schwartz Rounds is an example of reflective practice in action. Dr. Rita Charon’s Narrative Medicine movement uses the power of art for clinicians to share their stories. On Twitter, Dr. Colleen Farrell created #medhumchat, which is, “reflection, empathy, & connection in healthcare through discussions of poetry & prose.” You don’t have to be a physician to borrow some of these good ideas for your own workplace.

Everybody has a story. And everybody has to look after their own hearts so they can look after the hearts of others. This is where compassion is born.

Stories are complex creatures. Here are a few of my tips about storytelling in the professional realm:

- Keep it real. There is a fine balance between cheerleading and complaining. I try to share a positive story, then if I have a negative story, I always suggest what could have made it better. Constructive and authentic stories help lift morale and give a sense of hope.

- In groups, listen more than you talk. Check your own judgment and be as open-hearted as you can when listening to another’s story.Health care and human services are about serving others, so…

- Be careful of getting stuck in your own story. Sometimes your own story can overshadow or diminish the importance of the stories of the people you serve.

- A grief counsellor once told me: It is okay for people to have their story. And for you to have your story and for those two stories to be different.

- Be wary of comparing or minimizing stories. As someone once famously said: this isn’t the Olympics of suffering.

- Don’t steal other people’s stories for your own gain – especially people who have less power than you. (There are many authors who are guilty of this).

- Please don’t ignore other patient stories if you yourself become a patient. Share the stage and your microphone with others. Nobody’s story is more important than someone else’s, no matter their title or position.

- The only person you can represent with your story is your own fine self. Be mindful about speaking on behalf of others. (As a mother, I’ve been guilty of speaking on behalf of my children – especially my son who has an intellectual disability. I’ve been working hard to support him to share his own story instead).

It is always an honour for me to bear witness to someone’s story. I wish for more safe places where all kinds of people are guided to share their story. In the telling comes the healing. And we all need healing in our own ways.

While I’m a newbie to the cancer world, I have been the mom to a kid with a disability for 14 years. This doesn’t make me any kind of expert – it only makes me wary and tired.

While I’m a newbie to the cancer world, I have been the mom to a kid with a disability for 14 years. This doesn’t make me any kind of expert – it only makes me wary and tired.